MISSION

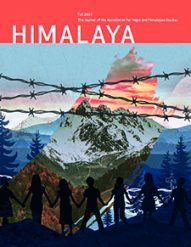

HIMALAYA is a biannual, open access, peer-reviewed journal published by the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies.

Interdisciplinary and trans-regional in scope, HIMALAYA covers all aspects of Himalayan studies, including the humanities and creative arts.

HIMALAYA publishes original research articles, short field reports, book and film reviews, reports on meetings and conferences, alongside literature and photo essays from the region.

Celebrating 50 years in 2022, HIMALAYA is the continuation of the Himalayan Research Bulletin (1981–2003) and the Nepal Studies Association Newsletter (1972–1980).

read moreNEWS

The Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies is pleased to announce that Dr. Jeevan Sharma and Dr. Michael Heneise will be the next Co-Editors of Himalaya. Dr. Sharma is a Senior Lecturer in South Asia and International Development at the School of Social and Political Sciences at the University of Edinburgh. He is as an executive committee member of the Britain Nepal Academic Council and the British Association of South Asian Studies. He is also sub-editor of South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies. Trained in Nepal, India and…

read morePhoto Essay

-

-

-

-

-

5. How We See Ourselves Where We Are:

In the last decade, there has been a transformative impact of smart phone’s regulation of people’s relationship to space, to self, each other, and the colonial police state. These digital devices with front and back facing cameras connected to social media (Instagram, Twitter, Facebook, YouTube) produce public representations of Kashmiris, as memes, photographs, and videos that are both live and post-dated.

In public spaces and places, in playgrounds, parks, by lakesides, people watch themselves with selfie cameras. They can view, re-view, and edit how they view themselves and are viewed.

They are aware they are being watched as they watch themselves. They may be grieving, in mass public funerals, or as shown here, in the park, out in the sun, having fun, sparkling in their smiles. They are not just dying, or dead. They are resilient. They retain their images, videos, stories, and distribute these images to each other, or to the ‘world wide web’ audience at the right moments.

They are self-determining how they are represented and seen.

Kashmiris use this medium to do digital story-telling, report their version of events, exercising agency which they previously had limited access to under traditional domestic and global corporate media and publishing platforms. Evidently, the power of this medium in the hands of the Kashmiri public is treated as a threat by the colonial state, as it easily holds them accountable on the world stage with respect to the legitimacy of the systematic use of violence and weapons against Kashmiris. There is also systemic repression of native Kashmir journalists and media platforms. The colonizer policies police and restricts what information reaches the rest of the world from within Kashmir, about Kashmir.

The response by state authorities has been to impose bans on internet and social media, as well as criminalize individuals and particular neighbourhoods with targeted crackdowns on individuals who articulate dissent to the status quo. There is cyber surveillance, and silencing faced by journalists and the general public. Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram have all sent notices to Kashmiris to remove digital content that the state demands, whether or not it violates the United Nation's Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, or Freedom of Information, and Freedom of Expression.

As I witnessed these moments, I considered what determined what versions of us we don’t want seen, shown, photographed, or watched in public spaces? Who and what made us believe certain versions of ourselves are undesirable in public spaces? Who is more visible, and why? Who is less visible, and why? Who does not have access yet to even this medium of self-representation? Why are some representations about Kashmiris invisiblized, and others hyper visiblized? "/> -

-

7. Pathraao – Responding From A Rock Hard Place:

red cheeks,

blood shot eyes,

red is the color of chillies

drying in the golden sun

to grind,

red is on the mind.

rickety rocks,

red tick,

red tock,

red blood,

red shots,

one red head off,

one red head drops.

visible is the

red is on the roads,

blocked with red rocks.

Throwing rocks is a form of protest in public spaces for at-risk populations like Kashmiri youth to express dissatisfaction or dissent in a repressive war zone. Where the normalized patterns of everyday life include injured, disappeared, or missing kin and relations turning up murdered, dead, and buried, it’s an expression of anger, rage, and refusal to accept the status quo and systemic injustices by the youth. Rather than position these youth in their rightful context, these Kashmiris (primarily youth) doing ‘pathrao’ (throwing rocks) are presented as part of a colonial narrative of ‘those violent delinquent Kashmiris’ by the popular corporate media in India, and those seeking to repress public display of protests.

In a war zone where the military and police are found in every corner carrying a loaded gun, the use of which they are unlikely to be held accountable for by colonial state laws, the use of rocks by unarmed people to articulate a response is presented as abhorrent, and shocking ‘juvenile Kashmiri crime.’ In the past decade, a new set of laws/policies as well as programs have been instituted to criminalize Kashmiri youth who engage in doing pathrao, pathologizing their choice rather than critically situating them in their appropriate context of being at-risk youth in a war zone. These youth are incarcerated for short to long-term sentences. They are eventually offered (policed) reform programming, where they are required to demonstrate that they will abandon their ways characterized as ‘criminal’. A genocidal policy of the Indian regime: these Indigenous children are forcibly removed from their families.

Some still throw rocks, after returning. Those who are labelled second time offenders face harsher sentences, and sometimes face arbitrary, lawless, indefinite incarceration under the Public Safety Act.

There are dimensions to the pathrao beyond the binary of seeing pathrao as anti-colonial resistance: an articulation of dissent and refusal of injustice and indignities, or alternatively the colonial narrative that: these youth are engaging in criminal behaviour. Those who experience pathrao will tell you that the rocks don’t always just hurt who they’re intended to hurt, who they’re meant for. To me, these rocks articulate another form of self-determination: we throw rocks at your policy decisions of trying to erase us from our land. Where freedom of expression using words can result in indefinite incarceration for journalists or academics, throwing rocks is another form of expression for a repressed population, articulation of self-representation, a distinct type of reclamation of social space and of power. "/> -

8. Mountain Goats - Mapping Kashmiri Land, Ancestral Memories, and Stories:

If they spoke, what would the Kashmiri Mountain goats tell us about the silk routes in the Valley which is now a war zone? How are the routes of seasonal migration with the Gujjar families impacted by the war? Are the animals aware there is a war going on? Will the young ones ever know a time without war? Do they duck, and lay low at the sound of gun shots?

Animal herds of mountain goat, sheep, with ponies and dogs are not just ordinary migrating animals. In Kashmir, what we observe everywhere are beautifully mowed landscapes. The landscapes, where the vibrant green grass in the commons is trimmed in spring, summer, and fall, is not achieved by heavy-duty lawn mowing machines. Instead, it is achieved by the grazing of these migrating animals, whose petite feet and excrement pellets keep the soil fertilized. The animals on the move stay healthy as well.

The war has not been able to stop the seasonal migration, the grazing, or the bowel movements that lead to fertile health of the soil. However, the commons space is increasingly under attack by corporate interests inside and outside Kashmir, bought and sold, and hyper policed and regulated by the settler colonial Indian military state.

The intersection of communal and colonial violence in India affects the migrating Bakarwal families who are primarily Muslim, and targets of Hindu supremacists, especially in the Jammu region. For example, it was within this context that in January 2018, Asifa Bano, an 8-year old Muslim girl belonging to a Bakarwal family, was kidnapped and gang raped in a private Hindu Temple by Hindu nationalists in Rasana, near Kathua. The case led to significant upheaval in Kashmir, with many sectors of civil society protesting the gross injustices in how the case was handled.

While Bakarwals navigate risks to their survival in unique ways in the face of war, these remain the same old silk routes their ancestors travelled, and communicated knowledges about how to travel the pathways safely via the DNA of the migrating flocks intergenerationally. Kashmiris have had relations with the sacred mountain animals since time-immemorial. The animals Bakarwals shepherd have clothed and fed Kashmiri and non-Kashmiris since time immemorial. They represent self-determining continuity of tradition despite the odds against them, such as the increasingly colonial privatization of communal Kashmiri land. "/> -

9. Noises that Keep You Awake - The War Doesn't Stop at Night:

Experiencing Kashmir as a war zone at night is complex. What does the night permit and limit?

It sounds like echoes of hundreds of ping pong balls dropping. Are these machine guns going off again, people ask. Some lay in bed, half asleep, wondering, ‘are these trauma hallucinations’? They will know in the morning. Some go back to sleep, and others can’t fall asleep. With agitation, sleeplessness, some pick up the mobile phone to check if the mobile internet has snapped. If yes, they conclude that those must have been machine guns.

Next set of concerns, who was killed? How many? Why? Is there a curfew/hartaal/shut down tomorrow where I live, or where I am going? Does that mean all plans are cancelled? Will businesses remain open or will they be closed? Are schools open or closed? Will I make it alive if I go out?

In the villages of Kunan and Poshpora, the military ordered mass rapes of Muslim Kashmiri women during the night in 1991 (Mushtaq et al 2015). When you hear a woman’s loud cries at night in a Kashmiri neighbourhood, you wonder what violence has met her. Rejecting the narrative of being just the victimized, these women have been resisting and demanding justice for more than two decades, without success in the Indian legal system. The Indian soldiers who perpetrated this sexual violence to terrorize the locals as a weapon of war, they enjoy impunity from having committed war crimes.

What does the night permit, and limit?

Nights turn into days, days turn into nights, and war crimes are protected by legalized impunity. There is zero accountability. Despite this, radical Kashmiri anti-colonial resistance and self-determination looks like actively seeking, and demanding justice, dignity and accountability anyway. "/> -

10. Freedom of Expression:

I witnessed Kashmiris rejecting the colonial state order on walls across Kashmir, with messages such as ‘Go India, Go Back.’ It was also reflected on the back of a car, and on the title of a burnt-down store. The back of the car read, “We Don’t Surrender / We Win Or Die,” and on the burnt store it read, “WAR TILL VICTORY.” I noticed that Kashmiris exercise the freedom to live and express themselves, before they experience an impending unjust murder by the Indian colonial occupier. Despite the expected violent backlash by the Indian military or police state, this visible political expressions of self-determination in Kashmir was still observable in September 2018. The frequency of witnessing these displays depends on the political climate and the neighbourhood of the Valley you are in.

Economically well-off neighbourhoods and communities enjoy greater human security in Kashmir; called ‘collaborators’ or ‘clients,’ their proximity to colonial power often entails greater intimacy and dependency on the colonial-masters.

I see self-determining Kashmiris humanize themselves by feeling the trauma wounds, fear, and moving past the fear by articulating their movements demands despite the colonial surveillance state repression and violences. "/> -

11. Karsa Adjust:

This photograph illustrates a type of power exercised through social solidarity. In Kashmir, you witness it in the face of trying circumstances, despite the colonizer financing systemic infiltration efforts to divide Kashmiris. The popular phrase ‘adjust karsa’ (one translation of karsa is: make it happen) is often evoked as a trusted Kashmiri saying when trying to create space when there might not be any. I imagine here that these men might have said to each other, one by one, adjust karsa, on an evening commute to home when travelling by this bus.

As an exercise in hospitality, it is not limited to Kashmiris supporting each other, it is also extended to anyone – Kashmiris and non-Kashmiris alike - who are perceived to experience a relative under-privileged positionality in a social circumstance. Sometimes the adjustment is uncomfortable; people adjust even when they do not necessarily want to.

‘Adjust karsa’ is what the elder woman at the hospital who needed to sit down might have said to squeeze in to sit on the bench. It is what the bodies that piled up to protect each other from cold did during a mass funeral of a young man, when there was not enough room to get a clear view of the procession. It is what people huddled together in-community to take heat from a burning fire may have said, just to get a little closer to warmth.

Kashmiris have collectively adjusted to uncomfortable and trying social circumstances as a temporary coping mechanism, but ultimately, what they want is justice, dignity, and security. What does self-determined justice, dignity, and security look like from a Kashmiri standpoint? As the time-old Kashmiri protest chant demands: ‘hum kya chahte,’ what do we want, the response has always been: ‘Aazadi,’ liberation. "/>