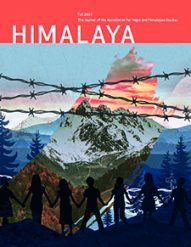

Photo Essay

A Day in the Life of a Herder in West Sikkim

While preparing dinner, Aitamaan turns on his prized transistor radio, which receives a distant signal coming out of Bhutan. All through the night, he tends to the fire and fidgets with the radio signal. On this night, his dogs are barking and restless—they know out beyond the light of the fire a wild animal is somewhere in the dark.

Sheep, like other livestock species, often require a salt supplement to their diet to help regulate their intake of fodder, to reduce the chance of overeating, and help keep them healthy. Aitamaan Limbu distributes salt to his herd on a weekly basis.

Here, Aitamaan collects sheep milk using a dhundheri. The milk is used for making ghue, a kind of butter, and is often sold or given in exchange in nearby villages. Sheep milk is believed to have medicinal properties in the region and is highly valued by locals.

At around 3:00pm, it is time to collect the herd and return to the goth. If the shelter has just been set up, like the day of our visit, Aitamaan will also need to chop and collect fern leaves to create a field of bedding for the sheep.

Meals are often kept very simple to save time and energy. Most meals consist mainly of rice. The herder will travel with a two-month supply of rice and will often purchase additional rations and supplies when traveling through a village or settlement.

After the morning’s tea, Aitamaan starts moving the herd to graze in the nearby forest. He prefers to keep the herd within one or two kilometers of the goth. He also starts to collect fodder for the lambs and sometimes for elder sheep who are tied up back in the camp. If the sheep are grazing near agricultural lands, particularly cardamom fields, he will also need to spray the crops with wet cow dung in an effort to prevent the sheep from grazing.

Sohang is a fifteen-year-old boy who has only been working in the goth for a few days. Aitamaan Limbu has already given him a lamb and has promised him an additional twenty thousand rupees at the end of a year’s work.

A normal day for Aitamaan starts at 4:30am. He makes tea for himself and his helpers. These helpers are mostly younger boys who get a monthly salary for helping with the herd, collecting fuel and water, and managing the daily chores. At the end of a year’s service, each boy receives a lamb to return home with.

A temporary shelter used by pastoral herders during seasonal, transhumant migration is locally known as goth. Prior to the Sikkimese state’s grazing ban, herders would stay in more permanent structures. But now new rules and regulations require herders to carry with them temporary shelters. These shelters are often simply a plastic sheet suspended over wooden beams and tied down with the ropes. Within the goth, the herder will store his possessions, which may include a woven mat to sleep on, an assortment of pots and cooking utensils, a lantern, and a transistor radio. Other possession commonly found in a goth include a dunderi, a wooden cylinder used to collect sheep milk, and a small knitted bag for salt known as a dapcha.

Sheep herding has been a traditional practice in West Sikkim. While some of the other livestock species like dzo (yak and cow hybrid) and horses were introduced in late 1950’s for tourism, sheep rearing has had its social and cultural significance in a self-sustained pastoral community of West Sikkim. The economic value of sheep rearing is primarily dependent of selling lamb and wool. Locals also believe that the ghue, butter of sheep milk has a lot of medicinal properties.

Aitamaan Limbu has been living on the mountainsides of Sikkim all his life. He used to travel across the temperate and sub-temperate forests and pastures of West Sikkim with his father’s cow and buffalo herd. As a young man, he would help collect firewood, prepare meals, and gather the animals in the evening around the herder’s hut, locally known as a goth. Today, he has close to one hundred and fifty sheep that he rears year-round. In the summer they graze the high alpine pastures and move in the winter to the temperate and sub-temperate forests of the comparatively lower altitude.

By Rashmi Singh

Photos by Jonathan Duncan

Aitamaan Limbu is one of the last few sheep herders in the West Sikkim, situated in the Eastern Himalaya of India. In the year 2002-2004, when a state policy banned most grazing and pastoral herding in the protected areas of Sikkim, Aitamaan Limbu sold his cattle and buffalos in the villages of Nepal adjacent to Sikkim’s international borders. However, the state continued to grant a few permits to herd smaller animals like goat and sheep in the region, so he then took up a herd of sheep. This is a photo essay explores a day in the life of one of the last few sheep herders in and around the Khangchendzonga National Park of Sikkim.

Pastoral livelihood and role of livestock grazing has been a question of great interest and long-standing debates in the rangeland conservation literature across the high-altitude regions of Central and South Asia. While the ecologists have continued to blamed livestock grazing for rangeland degradation, studies focusing on the social dimensions of the natural resource use by the pastoral communities have highlighted the critical role of traditional ecological knowledge and local institutions in assuring a sustainable management of the natural resources. It is in this debate lies the genesis of many such stories of removal and declined access of pastoral communities to their traditional grazing ground.

The idea for this project came when I was conducting research for my PhD in the remote regions of West Sikkim. I was keen in exploring the changes and continuities in the pastoral cultures of West Sikkim and document relationship that the herders have had with the forests and rangelands of Sikkim. For that, I had to conduct an ethnographic study of the last few pastoralists in the region, in addition to numerous ex-herders who had to leave pastoral practice post grazing ban implementation in Sikkim. This research required days of stay with the sheep herders who were continuing to rear their animals in West Sikkim. During my research, I had a chance to closely explore the life of these herders. While it was a day and night of experience and learning, I was most curious in understanding the rational of the resource use. During my time with these herders I realized that they had a well-prepared annual plan of natural resource use based on the seasons, availability of fodder and preference of altitude by the animal in different seasons. Day to day movement also depended on a number of other factors like proximity to the nearest villages, agricultural land, water resource availability, threat to predators. However, what was more exciting for me to live a day, and many days of a pastoralists myself and document how a day of the sheep herder looks like?

While conducting research, I met an American photojournalist, Jonathan Duncan, who joined me as I set off into the forest to interview Aitamaan Limbu on the periphery of an adjacent village and document a day of a sixty-three-year-old man who has been living with his animals in the forests and pastures of Sikkim for more than four decades. In spending any significant time with someone continuing to live a pastoral existence, one is struck by the considerable social and ecological stress under which they live. Livestock rearing requires a day and night effort. It also requires a deep knowledge of the natural systems that can only be acquired through years of direct experience living with your animals on the land. Aitamaan Limbu knows the seasons, the grasses, the contours of the landscape, and above all, his animals. The hope for this photo essay is to provide a window into the life of a sheep herder from the Eastern Himalaya, and to record a bit of the collected wisdom passed down from generations of people who have lived a pastoral existence in the forests and grasslands of the Himalaya.

This PhD research has been approved by the Research Studies Committee at Ambedkar University Delhi.

Rashmi Singh ([email protected]) is a PhD scholar at the School of Human Ecology, Ambedkar University Delhi. She has been conducting research on the pastoral communities of the Eastern and Western Himalaya of India for more than five years. She is primarily interested in documenting the changes and continuities in the pastoral systems of Indian Himalaya in the backdrop of the socio-political changes. For her PhD she is studying the politics of rangeland conservation in Sikkim and exploring the influence of the state led conservation intervention on the pastoral societies and rangeland ecologies of Sikkim.

Jonathan Duncan (j[email protected]) has over twenty years’ experience working as a professional photojournalist. His work has taken him through many of the world’s most remote geographies and cultures, and is driven by a passion for telling stories of how different people relate to and live within the land. He is the Creative Director of the digital content and production company Alpine Vision Media, and has served on the faculty of the Art Institute of Portland, Western Washington University, and Westminster College, where he is currently the adjunct professor of Adventure Media and Photography.