Photo Essay

Glimpses from a Monastic School in Zanskar

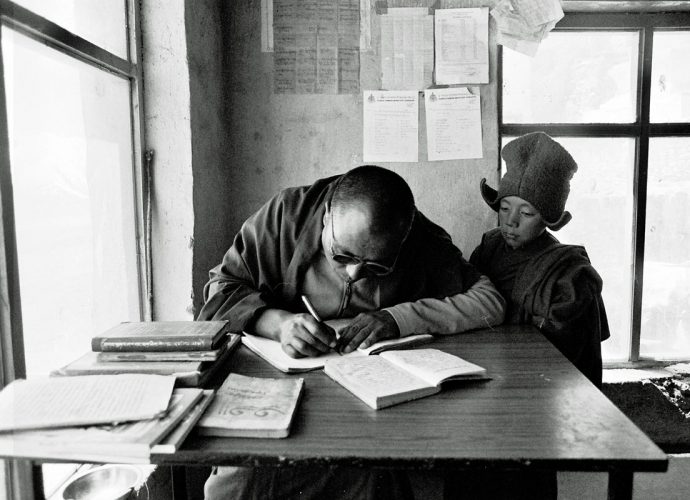

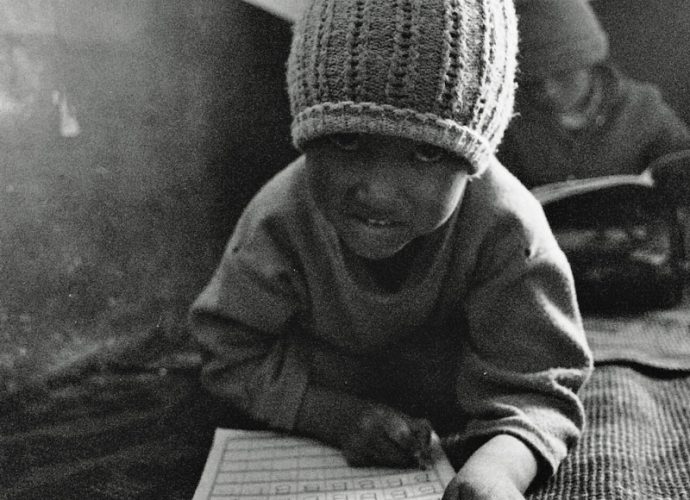

A Tibetan lama from Kham, who is a long-term resident at Karsha monastery, teaches a young Zanskari monk Bod yig (Tibetan script) by writing model sentences in the student’s notebook, which the young monk then needs to carefully and diligently copy. In a traditional Tibetan-style monastic school, learning happens predominantly through continuous repetition and memorization. While the perpetually practiced formulae are inscribed into student’s long term-memory, the discernment of meaning is treated as a secondary effect of a continuous and progressing learning process. It is not assumed it should be there from the beginning. The motto seems to be: ‘Learn it well first and then you can understand it’.

Even though Karsha monastery is the biggest and wealthiest in Zanskar, the school classroom conditions are basic (as of 2008). The rooms are not heated, and students traditionally sit and study on the floor.

On the opposite hill, the nunnery school day begins with a Manjushri (Buddhist patron of wisdom and learning) prayer recited out loud by a group of young girl-students, under the watchful eye of Tsering Namgyal, a resident monk-teacher from neighboring Ladakh. The lama has been sent to Zanskar by the Central Institute of Buddhist Studies (CIBS) near Leh. The teaching position in remote and underdeveloped Zanskar, far away from family and friends, is seen more in terms of a burdensome undertaking, rather than a reward by the young monks. Hence, finding a teacher for the gompa school often proves to be a difficult task, even though the monk teachers are provided with boarding, lodging, and a regular salary for the job, as well as complete freedom in their classroom curriculum design.

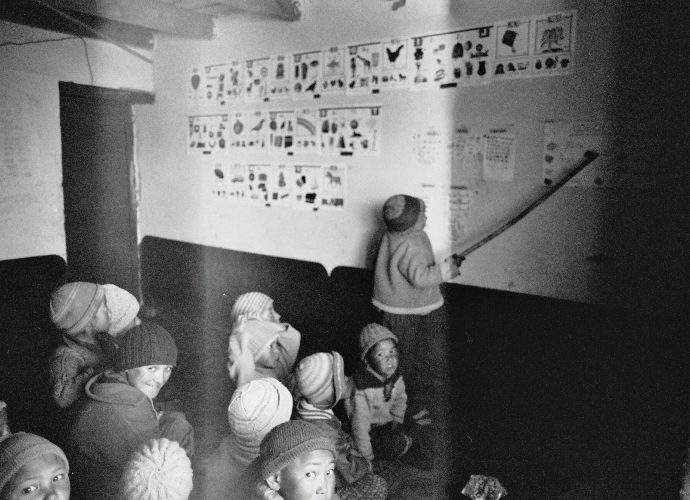

In the nunnery classroom, little Dolma is learning the English alphabet. Bananas are rarely available in the highland semi-desert, yet they are a standard item in Indian schoolbooks for English. Many items like this function on a somewhat abstract level for Zanskari children. The images of objects and concepts from the wider world travel faster than direct experiences of these things, making language learning abstracted from the surrounding everyday reality. At the same time, books are providing children with a simplified glimpse of what might lie beyond their local area.

Each student takes turn to play the teaching assistant’s role, speaking the material out loud in front of the class, pointing at its visual representation and waiting for other students to repeat.

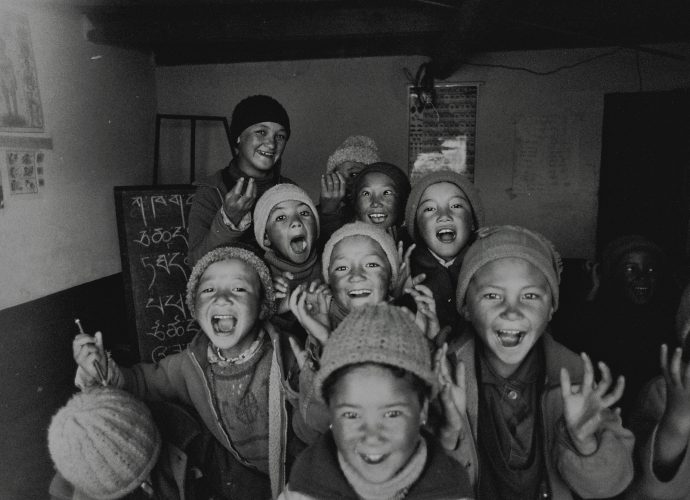

Dolma and Gachat sitting cross-legged on the carpeted floor in the nunnery classroom during weekly oral presentations. Once a week, usually on Saturday, all the girls gather together to present what they have learnt in the past week, in front of their schoolmates and the teachers. They are free to choose any subject, language or topic, as well as the duration of their presentation. They just need to recall something they remember, and tell it to their peers. Many young nuns are shy, especially in front of monks, so to practice presentation skills and public speaking in front of larger groups is an important educational task.

At the end of the presentations there is a performing reward: the singing and dancing of local Zanskari songs. It is a happy moment of releasing the body from the sitting constraints, which allows a freedom of expression through movement and group singing.

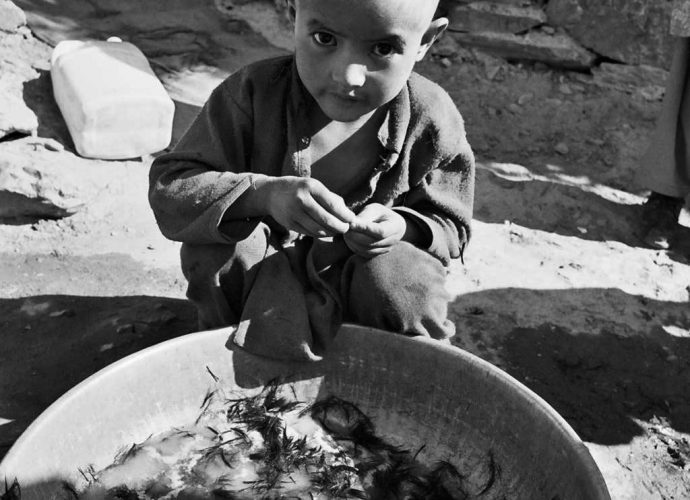

Students clean their classroom carpets after the long winter school-break. In the harsh Zanskari winter months, with temperatures occasionally dropping down to -30 degrees Celsius, students from the nunnery enjoy a long holiday and spend winter with their families in the surrounding villages. There is no heating available at the school, making teaching and learning in the coldest months of the year impossible.

Gatchat vigorously beats the classroom carpet to remove the dust that gathered over the winter break. Spring has come and the new season for learning begins. Students participate in the upkeep of the school, treating it as fun, rather than a chore.

by Marta Normington

In the remote Himalayan region of Zanskar, access to quality education still remains a challenging task. High mountain valleys lying further away from the main road arteries have to rely on local, often understaffed and modestly equipped schools. The regular educational migration of older children is common. Children and youths from distant mountain villages head towards larger educational centers in other regions, which are often geographically and culturally different from one’s own home.

The educational care of the younger children is oftentimes taken up by local Buddhist monastic schools. Even though the conditions are basic, these schools still manage to provide entry-level classes in Bod yig (Tibetan script), English (and sometimes Urdu), and general knowledge, as well as hot lunches for their students and teachers. Not all children that attend monastic schools will become monks or nuns, yet some do. Religious education opens up an inexpensive—and, for some, the only possible—way to higher studies, as well as an opportunity to travel beyond the region and see the wider world. Not only do monastery schools not charge the high tuition fees of local private schools, the possibility of a career in internationally active and multinational Tibetan Buddhist institutions, coupled with the local prestige of having chosen a religious path in life, may also be a tempting route towards intellectual, spiritual and social advancement. In times of precarity, these institutions offer a rare promise of having one’s life-long needs taken care of by a community of religious practitioners.

In 2007-2008 I spent almost a year living and working in a small Buddhist nunnery in Karsha, Zanskar. The nunnery runs a school for local girls with the financial help of an international NGO. There I was a teacher of English for the young nuns-to-be, and with a background in photography and arts, I also became a documentarian of the daily life happening around me at the time. This photo essay is a visual narrative from my time at the school, providing a few glimpses of what life in a monastery school may look like for the young students. It sheds some light on the life and learning process at two small monastic schools in the area. The photographs presented here were taken during my time there, and I often wonder how the life at the school has progressed since I left the gompa. One day I hope to travel back to the area to find out.

Marta Normington is a visual artist, photographer, and independent researcher currently based in Munich. She holds an M.F.A. in Photography and Multimedia from the University of Arts in Poznań, Poland, and an M.Sc. in Cross-Cultural Psychology from SWPS University, Warsaw. She also studied Documentary Photography at the University of Wales, UK, as well as Tibetan and Mongolian studies at the University of Warsaw. She travels regularly between Asia and Europe.