Photo Essay

Networked Objects

Lime Box or trimi

Bhutan

Late 19th or early 20th century

John Claude White collection

Courtesy of National Museums Liverpool, 56.27.232

John Claude White presented his Tibetan and Himalayan objects based on their aesthetic values. His collection not only contained religious objects, but objects owned and coveted by the aristocratic elites of the Himalaya. He especially respected the skills of the region’s metal workers and silversmiths and his collection is notable for its weapons and armour (some taken during the bloody campaign of Younghusband in 1904). He was also gifted high status pieces by the ruler’s of Sikkim and Bhutan, including a number of lime boxes or trimi. John Claude White made diplomatic visits to Bhutan in 1905 and 1907 and these lime boxes are likely to have been presented to him as diplomatic gifts during one of these Anglo-Bhutanese encounters.

“Art Specimens – III”

Originally published in Sikhim and Bhutan by John Claude White 1909.

Image supplied by Beryl Hartley

When Himalayan and Tibetan objects became mobile and moved into colonial worlds they often took on new meanings. Objects made for religious, cultural, military, mercantile and diplomatic reasons became something else in colonial hands. Objects in this new context were to be understood as a part of the wider imperial project to know places that were, or could potentially be, colonised. Alongside preserved botanical cuttings and hunted birds and animals, objects also became specimens; in John Claude White’s case ‘art specimens’. They were collected and assembled into collections not only to make visible the owner’s status as a Himalayan expert due to their rare access to unusual objects. But these objects were also important sites for study, collected in the expectation that information could be gathered from them that would shed light on difficult to reach places and the ruling elites who governed there. As can be seen in this image, colonial officers curated their collections long before they arrived in the museum, forming ideas about certain types of objects and how they should be grouped and understood.

Pema Tashi (cameraman), Sonam Wangdue (interviewer) and Kundeling Thupten (performer)

McLeod Ganj, Dharamshala, India

25 March 2015

Photographer, Emma Martin

As part of NML’s collecting project Tibetan Realities: Collecting Tibet and its Diasporas, the author attended the 20th Shoton (Tib. zho ston) festival held at McLeod Ganj, Dharamshala in Himachal Pradesh in March/April 2015. Over the course of two weeks 12 troupes from across South Asia came to perform traditional and newly commissioned operas at the Tibetan Institute of Performing Arts (TIPA). I worked with Tibetan cameramen and producers Pema Tashi and Sonam Wangdue to record this major event for inclusion in the NML exhibition, Tibet: Dreams and Realities. Here, Pema Tashi and Sonam Wangdue are conducting an interview with acclaimed ache lhamo performer, Kundeling Thupten. 82-year-old Kundeling Thupten formed an ache lhamo troupe in 1959 after escaping into exile. He lives in Bylakuppe, South India and still performs for the Bylakuppe Lhamo Association.

Red Demoness Mask or Marpo Srinmo

McLeod Ganj, Dharamshala, India

2011

Courtesy of National Museums Liverpool, LIV.2012.40.15

Since 2011, NML has been working with the Tibetan Institute of Performing Arts (TIPA) based in Dharamshala, Himachal Pradesh to create a material and visual archive of ache lhamo (Tib. a lce lha mo) for the museum’s permanent collection. While the intangible heritage of ache lhamo - a Tibetan opera - has received growing attention, the material culture of ache lhamo is underrepresented in UK museum collections. Before the 1950s, ache lhamo was performed by peripatetic actors who moved from town to village criss-crossing Tibet, Sikkim and the wider Himalayan region. Since the 1980s ache lhamo has been remade and has become a visible marker of Tibetanness in exile.

Votive plaque featuring Durga

Nepal

18th century

Courtesy of National Museums Liverpool, 53.87.54

This devotional plaque which features Durga is made from wood, covered with copper gilt and fitted with turquoise and precious stones. The quality suggests it was made for a wealthy Hindu devotee. It is fitted with vajra (Tib. rdo rje, a ritual object that symbolises the properties of the thunderbolt and the diamond – the Sanskrit meaning of vajra) recognised by Hindus, Jains and Buddhists. The inclusion of the vajra makes the cultural and religious exchange of ideas and practice visible. But there is another possible story that the plaque has yet to tell. This one reflects the practice of museum curation and the museum curator’s interest in reconnecting objects to their biographical record and the relationships they once had to people and events. In this case, the unsolved clue comes in the form of a collector’s name noted on the object’s museum label. The collector/owner of the plaque was Sir Charles James Stevenson-Moore (1866-1947) an Indian Civil Service officer. From 1904-07 he was the Inspector General of the Bengali Police force, responsible for the security detail that watched over the ninth Panchen Lama, Thupten Chökyi Nyima (1883-1937) during his visit to Calcutta in 1905-06. Was this high status item then one of the gifts that the Panchen Lama brought to Calcutta for the British Indian government. (Gifts given by dignitaries from across the Himalayan and wider Asian worlds were often stored in specific gift treasuries in Tibet so that they could be given again to unconnected dignitaries at future diplomatic meetings). Had Stevenson-Moore subsequently bought it at auction or from the British India Treasury when the Tibetan gifts were sold off? Had this plaque criss-crossed the Himalaya during its devotional life? This is just one of many hundreds of object biographies still to be uncovered.

Gangtok Residency

1908-1918

Photographer Unknown

Courtesy of a Private Collection

When Sir Charles Bell (1870-1945) was appointed to the post of Political Officer of Sikkim, Bhutan and Tibet in 1908, he became the highest-ranking imperial officer in the eastern Himalaya. His colonial base was the Gangtok Residency in Sikkim. The house built by his predecessor, John Claude White (1853-1919), was situated close to the Chögyal (Tib. chos rgyal) or ruler of Sikkim’s palace and represented the British India government’s imperial power in the region. Bell cultivated his scholarly persona in the Himalaya and during his residency in Sikkim he designed a series of rooms (see Figure 2) that emphasised his Himalayan knowledge. He created a series of shrine-like mantelpieces that displayed the objects he had purchased, commissioned and had been gifted during his tenure. Including as can be seen here the senge.

One of a pair of senge (guardian lions)

Made in Patan, Kathmandu Valley, Nepal

1908, inscribed with the Vikrama year 1965 (1908)

Commissioned or bought by, Rai Sahib Laksminarayan Pradhan

Gifted to, Sir Charles Bell, Political Officer for Sikkim, Bhutan and Tibet (1908-18)

Courtesy of National Museums Liverpool, 50.31.20a+b

Rai Sahib Laksminarayan Pradhan, the son of the first Newar settler in Sikkim and subsequently powerful landlord either commissioned or bought the senge shortly after they were made. He gifted them to Charles Bell soon after. The year 1908 is significant as this was the year Charles Bell was appointed to the post of Political Officer in Sikkim and the year Pradhan received his imperial title, ‘Rai Sahib.’

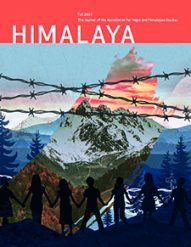

by Emma Martin (Senior Curator of Ethnology, National Museums Liverpool)

Objects and their archives make tangible networks and connections that might not be obvious from other sources. These material records connect people, places and practice in unexpected ways. This small selection of objects from the Himalaya collection at National Museums Liverpool (NML) does just that. They tell of imperial encounters, the exchange of artistic and religious practice, the archiving of the Himalaya, and the continuation and preservation of culture in Himalayan exile.

The importance of material things in telling small-scale histories of empire and knowledge making is an important aspect of my work. My historical investigations into late 19th and early 20th century colonial collecting and its relevance to imperial knowledge making have greatly influenced my thinking on contemporary collecting. I am particularly interested in the political and diplomatic histories of Tibetan and Himalayan objects and their subsequent transformation into exclusively religious things when they enter the museum space. My aim is to bring a visual challenge to the long-standing imagining of Tibet in the museum that inevitably includes pseudo-shrines and religious narratives situated in a fixed pre-1959 ‘ethnographic present.’

In order to disrupt this imagining I am currently working on Tibetan Realities: Collecting Tibet and its Diasporas, a collecting programme for NML (funded by the Molly Tomlinson Memorial Fund and the Art Fund), which combines commissioning and collecting contemporary art and ephemera with collecting and recording in the field. This collecting project will result in Tibet: Dreams and Realities, an exhibition I am curating in 2016/17 which will combine the many historical and contemporary imaginings of Tibet, using NML’s internationally significant collection of Tibetan and Himalayan art and ethnography. These imaginings will be challenged by artwork from some of Tibet and its diasporas leading contemporary artists and documentaries from Tibetan students living in exile.