Photo Essay

sites of power differentials in Kashmir: self-determination as anti-colonial resistance under un-/polic/e/y-ed genocidal colonial social order

Policing (restricting and permitting) access to social spaces is one-way social mobility in Indian occupied Kashmir is regulated as a war zone. Here you see that a heavy metal door with barbed wires has been placed by the state to restrict access to a Buddhist monastery ruins (from approximately A.D. 78), on a mountain top in Kashmir. Looking beyond the barbed wires and gate, you see a glimpse of the Kashmir valley from this mountain top.

This gate symbolically reflects the militarized regulation of this Himalayan mountain valley range, where human mobility is controlled by militarized state’s determination of what and/or who deserves safety, as well as security. It is evident that the restrictions in place at these ancient monastery ruins is in part to regulate access to space, thereby securitizing space, and restricting/regulating undesired human activity, such as preventing the Bakarwal population of Kashmir from using it for grazing and rearing their sheep and mountain goat herds.

The militarized securitization of Kashmiri land by the genocidal occupying, colonizing Indian state has been presented by the colonizer as its inherent ‘security’ need, namely, control of the border and the Kashmiri population. However, the human subjects constructed to be ‘Indian citizens’, the Kashmiri people, are regular targets of violence by Indian military forces without civil court or judicial oversight. Kashmiris live under normalized insecurities due to a violent militarized colonial state social order, where war measure laws such as the Jammu and Kashmir Public Safety Act 1978 (PSA), the 1990 Armed Forces (Jammu and Kashmir) Special Powers Act, and the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (UAPA) serve to protect colonizing Indian military / paramilitary personnel domestically within India from committing what are war-crimes under international law. It is evident that ‘securing’ land is valued by the colonizing Indian regime, while Kashmiri lives are to be annihilated.

What the militarized state cannot regulate is the movement of Kashmiri birds and other species. They defy borders, defy imposed limits on their freedoms. Kashmiri ‘insurgents’, ‘rebels’, non-human lives do not demand freedom, they are free, because they act free. This is the spirit of Kashmiri self-determination; it is beyond the containment capability of a colonizing power."/>

1. Barbed Gateway:

Policing (restricting and permitting) access to social spaces is one-way social mobility in Indian occupied Kashmir is regulated as a war zone. Here you see that a heavy metal door with barbed wires has been placed by the state to restrict access to a Buddhist monastery ruins (from approximately A.D. 78), on a mountain top in Kashmir. Looking beyond the barbed wires and gate, you see a glimpse of the Kashmir valley from this mountain top.

This gate symbolically reflects the militarized regulation of this Himalayan mountain valley range, where human mobility is controlled by militarized state’s determination of what and/or who deserves safety, as well as security. It is evident that the restrictions in place at these ancient monastery ruins is in part to regulate access to space, thereby securitizing space, and restricting/regulating undesired human activity, such as preventing the Bakarwal population of Kashmir from using it for grazing and rearing their sheep and mountain goat herds.

The militarized securitization of Kashmiri land by the genocidal occupying, colonizing Indian state has been presented by the colonizer as its inherent ‘security’ need, namely, control of the border and the Kashmiri population. However, the human subjects constructed to be ‘Indian citizens’, the Kashmiri people, are regular targets of violence by Indian military forces without civil court or judicial oversight. Kashmiris live under normalized insecurities due to a violent militarized colonial state social order, where war measure laws such as the Jammu and Kashmir Public Safety Act 1978 (PSA), the 1990 Armed Forces (Jammu and Kashmir) Special Powers Act, and the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (UAPA) serve to protect colonizing Indian military / paramilitary personnel domestically within India from committing what are war-crimes under international law. It is evident that ‘securing’ land is valued by the colonizing Indian regime, while Kashmiri lives are to be annihilated.

What the militarized state cannot regulate is the movement of Kashmiri birds and other species. They defy borders, defy imposed limits on their freedoms. Kashmiri ‘insurgents’, ‘rebels’, non-human lives do not demand freedom, they are free, because they act free. This is the spirit of Kashmiri self-determination; it is beyond the containment capability of a colonizing power.

What you see here is a Kashmiri girl looking at Dal Lake from a car window.

By bearing witness, acknowledging, and documenting the facts of their living conditions, and by articulating the former to themselves and others, many Kashmiris engage in powerful acts of self-determination; they do this in spite of being expected by the domineering state to look from selective, permitted frames, or otherwise remain indifferent and sub-servient.

Looking beyond the barbed wires, barbed gateways, beyond limits of window frames, externally imposed narratives, dominant discourses and representations about themselves and their homeland, Kashmiris notice their suffering, and their strength.

Kashmiris voicing what they witness, what they want for themselves, their territories is form of self-determination. The colonial state routinely seeks to silence and repress these self-determining Kashmiri voices. When silencing does not work, they target and threaten to eliminate those doing the observing and speaking (UNHCHR 2018, UNHCHR 2019, Ahmed 2019a). While non-Kashmiri experts receive awards for their paternalistic or saviour-oriented gaze on Kashmir, vast majority of Kashmiris bear witness and speak without receiving awards and speak truth to power, as powerful people, anyway. Like this girl, the sun shines on generations of Kashmiri children growing up in war to become adults, and continue to bear witness to see themselves in all their complexity, articulating visions of self-determination as their inherent human right as an Indigenous people.

In spite of the corporate colonial statist media narratives dehumanizing Kashmiris, their religious identity as Muslims, falsely portraying Kashmiris Muslims as a delinquent group of people, Kashmiri Muslim women as helpless, or that India has won the war to retain Kashmir as part of its national imagination, is rejected by Kashmiris I know. This critical consciousness of a Kashmiri self that rejects colonizing narratives and representations, and asserts speaking from a place of a lived reality, lived story, lived truths, is another modality of self-determination. "/>

2. Watching, Witnessing:

What you see here is a Kashmiri girl looking at Dal Lake from a car window.

By bearing witness, acknowledging, and documenting the facts of their living conditions, and by articulating the former to themselves and others, many Kashmiris engage in powerful acts of self-determination; they do this in spite of being expected by the domineering state to look from selective, permitted frames, or otherwise remain indifferent and sub-servient.

Looking beyond the barbed wires, barbed gateways, beyond limits of window frames, externally imposed narratives, dominant discourses and representations about themselves and their homeland, Kashmiris notice their suffering, and their strength.

Kashmiris voicing what they witness, what they want for themselves, their territories is form of self-determination. The colonial state routinely seeks to silence and repress these self-determining Kashmiri voices. When silencing does not work, they target and threaten to eliminate those doing the observing and speaking (UNHCHR 2018, UNHCHR 2019, Ahmed 2019a). While non-Kashmiri experts receive awards for their paternalistic or saviour-oriented gaze on Kashmir, vast majority of Kashmiris bear witness and speak without receiving awards and speak truth to power, as powerful people, anyway. Like this girl, the sun shines on generations of Kashmiri children growing up in war to become adults, and continue to bear witness to see themselves in all their complexity, articulating visions of self-determination as their inherent human right as an Indigenous people.

In spite of the corporate colonial statist media narratives dehumanizing Kashmiris, their religious identity as Muslims, falsely portraying Kashmiris Muslims as a delinquent group of people, Kashmiri Muslim women as helpless, or that India has won the war to retain Kashmir as part of its national imagination, is rejected by Kashmiris I know. This critical consciousness of a Kashmiri self that rejects colonizing narratives and representations, and asserts speaking from a place of a lived reality, lived story, lived truths, is another modality of self-determination.

There is no gun free zone in Kashmir. In public spaces, Kashmiris are watched with heavily armed Indian regime’s armed men with loaded weapons. Who were these weapons purchased from? Who profited from arming these men with guns?

Kashmiris are routinely surveilled, and their autonomy is restricted in numerous ways. Their physical movement, online activities, and their phone usage data is tracked. After Aug 5, 2019, this autonomy was further obliterated with the dissolving of Article 370 and Section 35A of the Indian constitution, despite Kashmiri people’s decades of opposition and anti-colonial resistance to the proposed changes. In addition to routine restriction that hamper autonomy, land and membership rights to Kashmir have been obliterated by the colonial Indian regime by implementation of the 2020 Domicile Law, and subsequently putting Kashmiri land for sale for Indian broadly. This is intended to genocidally alter the demography of Kashmiris on their territory and expedite capitalist extraction.

Here, you see the ordinariness of the natives driving, walking, while witnessing themselves being watched by the military and police. While a Kashmiri man watches his phone screen, Kashmiris are being watched and ‘polic-y-ed’ digitally and in person by colonizers fear and censorship enforcement bodies holding loaded guns.

Under the colonial occupation in Kashmir, internet and/or mobile phone internet shutdowns are routinely placed as a blanket policy across the valley, and in select/targeted areas determined to have elements of insecurity (‘disturbed areas’ by individuals) and therefore requiring greater state sanctioned disconnection among the Kashmiri population. Both the physical and spatial curfews, and online restrictions block the ability of the Kashmiri people to engage in social and economic activities - such as engaging with businesses, community, family, health and wellness, or education. Some Kashmiris assert self-determination by using VPNs to mask their IP address on the internet, engaging in covert ways to share content and information that the occupying colonial Indian regime does not want them to share with each other, or the world. "/>

3. No Gun-Free Zone:

There is no gun free zone in Kashmir. In public spaces, Kashmiris are watched with heavily armed Indian regime’s armed men with loaded weapons. Who were these weapons purchased from? Who profited from arming these men with guns?

Kashmiris are routinely surveilled, and their autonomy is restricted in numerous ways. Their physical movement, online activities, and their phone usage data is tracked. After Aug 5, 2019, this autonomy was further obliterated with the dissolving of Article 370 and Section 35A of the Indian constitution, despite Kashmiri people’s decades of opposition and anti-colonial resistance to the proposed changes. In addition to routine restriction that hamper autonomy, land and membership rights to Kashmir have been obliterated by the colonial Indian regime by implementation of the 2020 Domicile Law, and subsequently putting Kashmiri land for sale for Indian broadly. This is intended to genocidally alter the demography of Kashmiris on their territory and expedite capitalist extraction.

Here, you see the ordinariness of the natives driving, walking, while witnessing themselves being watched by the military and police. While a Kashmiri man watches his phone screen, Kashmiris are being watched and ‘polic-y-ed’ digitally and in person by colonizers fear and censorship enforcement bodies holding loaded guns.

Under the colonial occupation in Kashmir, internet and/or mobile phone internet shutdowns are routinely placed as a blanket policy across the valley, and in select/targeted areas determined to have elements of insecurity (‘disturbed areas’ by individuals) and therefore requiring greater state sanctioned disconnection among the Kashmiri population. Both the physical and spatial curfews, and online restrictions block the ability of the Kashmiri people to engage in social and economic activities - such as engaging with businesses, community, family, health and wellness, or education. Some Kashmiris assert self-determination by using VPNs to mask their IP address on the internet, engaging in covert ways to share content and information that the occupying colonial Indian regime does not want them to share with each other, or the world.

In both large scale spaces and small corners occupied by the military, in the city centres or on the outskirts, it is written in white paint with red backdrop on walls across Kashmir, and it reads: “MILITARY AREA / YOU ARE BEING WATCHED / ARMED RESPONSE TO TRESPASSING”. Or in Urdu “Fougi ilaka, Aap ke upar nazar hai, bina ijazat ghusnay par fire hoga,” which ought to be understood as, ‘This is the Indian ‘military territory / we are surveilling you / entering without permission will be answered by gun fire.”

While the Indian state does not concede this internationally, it is affirming that this is a ‘war zone’ in the messaging announced both in Urdu and English across Kashmir: “you are being watched” in this militarized space, and that you will be attacked/fired at by the Indian military if you behave in a manner that is unsanctioned by the occupying military state. A panoptic imperial prison state surveillance (Foucault 2008) is in place in Kashmir. Here, the military determines/controls that freedom of mobility. Native Kashmiris accessing their own land freely is restricted by the colonizer as undesirable, impermissible.

There are barbed wires above the walls, and a green camouflage metal barrier with additional ring barbed wires going across with glass bottles hanging that are supposed to chime in case someone moves the barbed wires. There is also a tower for monitoring public activity. Similarly designed bunkers and posts exist across Kashmir, which are either bigger or smaller in scale.

The military has been present in Kashmir in an intensified capacity since the 1990s, with the current ratio reported to be an estimate of between 6:1 and 7:1 of civilians to an armed Indian state trooper. To care for the military, there are Indian military family settler colonies established, with schools, playgrounds, movie theatre, and other infrastructure, with high level security for them exclusively to enjoy safety. An example of such a colony can be seen in a prized location in Kashmir, on the periphery of the Airport in Srinagar. In comparison, only high-level officials in the Indian regime and business enjoy such security. Average Kashmiri civilians live in a state of colonially imposed insecurity daily. "/>

4. Ruling through Fear - Rationalized Panoptic Police Surveillance and Intimidation:

In both large scale spaces and small corners occupied by the military, in the city centres or on the outskirts, it is written in white paint with red backdrop on walls across Kashmir, and it reads: “MILITARY AREA / YOU ARE BEING WATCHED / ARMED RESPONSE TO TRESPASSING”. Or in Urdu “Fougi ilaka, Aap ke upar nazar hai, bina ijazat ghusnay par fire hoga,” which ought to be understood as, ‘This is the Indian ‘military territory / we are surveilling you / entering without permission will be answered by gun fire.”

While the Indian state does not concede this internationally, it is affirming that this is a ‘war zone’ in the messaging announced both in Urdu and English across Kashmir: “you are being watched” in this militarized space, and that you will be attacked/fired at by the Indian military if you behave in a manner that is unsanctioned by the occupying military state. A panoptic imperial prison state surveillance (Foucault 2008) is in place in Kashmir. Here, the military determines/controls that freedom of mobility. Native Kashmiris accessing their own land freely is restricted by the colonizer as undesirable, impermissible.

There are barbed wires above the walls, and a green camouflage metal barrier with additional ring barbed wires going across with glass bottles hanging that are supposed to chime in case someone moves the barbed wires. There is also a tower for monitoring public activity. Similarly designed bunkers and posts exist across Kashmir, which are either bigger or smaller in scale.

The military has been present in Kashmir in an intensified capacity since the 1990s, with the current ratio reported to be an estimate of between 6:1 and 7:1 of civilians to an armed Indian state trooper. To care for the military, there are Indian military family settler colonies established, with schools, playgrounds, movie theatre, and other infrastructure, with high level security for them exclusively to enjoy safety. An example of such a colony can be seen in a prized location in Kashmir, on the periphery of the Airport in Srinagar. In comparison, only high-level officials in the Indian regime and business enjoy such security. Average Kashmiri civilians live in a state of colonially imposed insecurity daily.

In the last decade, there has been a transformative impact of smart phone’s regulation of people’s relationship to space, to self, each other, and the colonial police state. These digital devices with front and back facing cameras connected to social media (Instagram, Twitter, Facebook, YouTube) produce public representations of Kashmiris, as memes, photographs, and videos that are both live and post-dated.

In public spaces and places, in playgrounds, parks, by lakesides, people watch themselves with selfie cameras. They can view, re-view, and edit how they view themselves and are viewed.

They are aware they are being watched as they watch themselves. They may be grieving, in mass public funerals, or as shown here, in the park, out in the sun, having fun, sparkling in their smiles. They are not just dying, or dead. They are resilient. They retain their images, videos, stories, and distribute these images to each other, or to the ‘world wide web’ audience at the right moments.

They are self-determining how they are represented and seen.

Kashmiris use this medium to do digital story-telling, report their version of events, exercising agency which they previously had limited access to under traditional domestic and global corporate media and publishing platforms. Evidently, the power of this medium in the hands of the Kashmiri public is treated as a threat by the colonial state, as it easily holds them accountable on the world stage with respect to the legitimacy of the systematic use of violence and weapons against Kashmiris. There is also systemic repression of native Kashmir journalists and media platforms. The colonizer policies police and restricts what information reaches the rest of the world from within Kashmir, about Kashmir.

The response by state authorities has been to impose bans on internet and social media, as well as criminalize individuals and particular neighbourhoods with targeted crackdowns on individuals who articulate dissent to the status quo. There is cyber surveillance, and silencing faced by journalists and the general public. Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram have all sent notices to Kashmiris to remove digital content that the state demands, whether or not it violates the United Nation's Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, or Freedom of Information, and Freedom of Expression.

As I witnessed these moments, I considered what determined what versions of us we don’t want seen, shown, photographed, or watched in public spaces? Who and what made us believe certain versions of ourselves are undesirable in public spaces? Who is more visible, and why? Who is less visible, and why? Who does not have access yet to even this medium of self-representation? Why are some representations about Kashmiris invisiblized, and others hyper visiblized? "/>

5. How We See Ourselves Where We Are:

In the last decade, there has been a transformative impact of smart phone’s regulation of people’s relationship to space, to self, each other, and the colonial police state. These digital devices with front and back facing cameras connected to social media (Instagram, Twitter, Facebook, YouTube) produce public representations of Kashmiris, as memes, photographs, and videos that are both live and post-dated.

In public spaces and places, in playgrounds, parks, by lakesides, people watch themselves with selfie cameras. They can view, re-view, and edit how they view themselves and are viewed.

They are aware they are being watched as they watch themselves. They may be grieving, in mass public funerals, or as shown here, in the park, out in the sun, having fun, sparkling in their smiles. They are not just dying, or dead. They are resilient. They retain their images, videos, stories, and distribute these images to each other, or to the ‘world wide web’ audience at the right moments.

They are self-determining how they are represented and seen.

Kashmiris use this medium to do digital story-telling, report their version of events, exercising agency which they previously had limited access to under traditional domestic and global corporate media and publishing platforms. Evidently, the power of this medium in the hands of the Kashmiri public is treated as a threat by the colonial state, as it easily holds them accountable on the world stage with respect to the legitimacy of the systematic use of violence and weapons against Kashmiris. There is also systemic repression of native Kashmir journalists and media platforms. The colonizer policies police and restricts what information reaches the rest of the world from within Kashmir, about Kashmir.

The response by state authorities has been to impose bans on internet and social media, as well as criminalize individuals and particular neighbourhoods with targeted crackdowns on individuals who articulate dissent to the status quo. There is cyber surveillance, and silencing faced by journalists and the general public. Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram have all sent notices to Kashmiris to remove digital content that the state demands, whether or not it violates the United Nation's Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, or Freedom of Information, and Freedom of Expression.

As I witnessed these moments, I considered what determined what versions of us we don’t want seen, shown, photographed, or watched in public spaces? Who and what made us believe certain versions of ourselves are undesirable in public spaces? Who is more visible, and why? Who is less visible, and why? Who does not have access yet to even this medium of self-representation? Why are some representations about Kashmiris invisiblized, and others hyper visiblized?

What you see here is an empty swing, repeated from three angles, emphasizing an empty space on the swing.

In a war zone where there is legislated impunity for armed forces, it is unsurprising that there are thousands of missing, murdered, or disappeared persons. In this dimension of living in a war zone, there is an ongoing experience of knowing someone has been killed, or disappeared, without ever receiving justice. There is an ongoing possibility of being the next person to become a statistic in this category. When loved ones do not respond to phone calls or messages, or returns home later than expected, family members fear the worse.

Even though India is a signatory to the United Nations Declaration on the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearances (2007), an estimated 8,000 to 10,000 Kashmiri civilians have been reported disappeared or missing between 1989 and 2006 alone (APDP n.d.). Founded by Parveena Ahangar, whose 16-year old son Javaid Ahmad Ahangar was picked up by the security forces (on August 18, 1990) and never returned, the Association of Parents of Disappeared Persons (APDP) has been providing support and doing advocacy for families of missing people since 1994.

Given the multitude of ways violence has permeated the everyday lives of Kashmiris, due to a prolonged ongoing war, another effect of trauma is an increase in rate of attempted suicides in the population. According to one study, between 2000 to 2008, 23% of all emergency room psychiatric visits in Kashmir were due to suicide attempts, where women represented a greater portion (Wani et al 2011). Deliberately controlled social conditions that drive them to such despair, these cannot be treated as merely suicides; the numbers of Kashmiris taking their own lives should instead be read as premediated, systematic colonial annihilation technique of used against the natives.

In this context, Kashmiris exercising power by remembering their loved ones, and refusing to give up in their pursuit of justice. For example, APDP organizes regular public gatherings with family members holding photographs of loved ones, reminding the state that they have not forgotten, and they will not let others forget. In this way, community power continues to refresh public memory. Refusing to let the forcibly disappeared by genocidal colonial Indian regime disappear from public memory, searching for them, and demanding justice is another articulation of Kashmiri self-determination. "/>

6. Visiblizing the Missing and Disappeared:

What you see here is an empty swing, repeated from three angles, emphasizing an empty space on the swing.

In a war zone where there is legislated impunity for armed forces, it is unsurprising that there are thousands of missing, murdered, or disappeared persons. In this dimension of living in a war zone, there is an ongoing experience of knowing someone has been killed, or disappeared, without ever receiving justice. There is an ongoing possibility of being the next person to become a statistic in this category. When loved ones do not respond to phone calls or messages, or returns home later than expected, family members fear the worse.

Even though India is a signatory to the United Nations Declaration on the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearances (2007), an estimated 8,000 to 10,000 Kashmiri civilians have been reported disappeared or missing between 1989 and 2006 alone (APDP n.d.). Founded by Parveena Ahangar, whose 16-year old son Javaid Ahmad Ahangar was picked up by the security forces (on August 18, 1990) and never returned, the Association of Parents of Disappeared Persons (APDP) has been providing support and doing advocacy for families of missing people since 1994.

Given the multitude of ways violence has permeated the everyday lives of Kashmiris, due to a prolonged ongoing war, another effect of trauma is an increase in rate of attempted suicides in the population. According to one study, between 2000 to 2008, 23% of all emergency room psychiatric visits in Kashmir were due to suicide attempts, where women represented a greater portion (Wani et al 2011). Deliberately controlled social conditions that drive them to such despair, these cannot be treated as merely suicides; the numbers of Kashmiris taking their own lives should instead be read as premediated, systematic colonial annihilation technique of used against the natives.

In this context, Kashmiris exercising power by remembering their loved ones, and refusing to give up in their pursuit of justice. For example, APDP organizes regular public gatherings with family members holding photographs of loved ones, reminding the state that they have not forgotten, and they will not let others forget. In this way, community power continues to refresh public memory. Refusing to let the forcibly disappeared by genocidal colonial Indian regime disappear from public memory, searching for them, and demanding justice is another articulation of Kashmiri self-determination.

red cheeks,

blood shot eyes,

red is the color of chillies

drying in the golden sun

to grind,

red is on the mind.

rickety rocks,

red tick,

red tock,

red blood,

red shots,

one red head off,

one red head drops.

visible is the

red is on the roads,

blocked with red rocks.

Throwing rocks is a form of protest in public spaces for at-risk populations like Kashmiri youth to express dissatisfaction or dissent in a repressive war zone. Where the normalized patterns of everyday life include injured, disappeared, or missing kin and relations turning up murdered, dead, and buried, it’s an expression of anger, rage, and refusal to accept the status quo and systemic injustices by the youth. Rather than position these youth in their rightful context, these Kashmiris (primarily youth) doing ‘pathrao’ (throwing rocks) are presented as part of a colonial narrative of ‘those violent delinquent Kashmiris’ by the popular corporate media in India, and those seeking to repress public display of protests.

In a war zone where the military and police are found in every corner carrying a loaded gun, the use of which they are unlikely to be held accountable for by colonial state laws, the use of rocks by unarmed people to articulate a response is presented as abhorrent, and shocking ‘juvenile Kashmiri crime.’ In the past decade, a new set of laws/policies as well as programs have been instituted to criminalize Kashmiri youth who engage in doing pathrao, pathologizing their choice rather than critically situating them in their appropriate context of being at-risk youth in a war zone. These youth are incarcerated for short to long-term sentences. They are eventually offered (policed) reform programming, where they are required to demonstrate that they will abandon their ways characterized as ‘criminal’. A genocidal policy of the Indian regime: these Indigenous children are forcibly removed from their families.

Some still throw rocks, after returning. Those who are labelled second time offenders face harsher sentences, and sometimes face arbitrary, lawless, indefinite incarceration under the Public Safety Act.

There are dimensions to the pathrao beyond the binary of seeing pathrao as anti-colonial resistance: an articulation of dissent and refusal of injustice and indignities, or alternatively the colonial narrative that: these youth are engaging in criminal behaviour. Those who experience pathrao will tell you that the rocks don’t always just hurt who they’re intended to hurt, who they’re meant for. To me, these rocks articulate another form of self-determination: we throw rocks at your policy decisions of trying to erase us from our land. Where freedom of expression using words can result in indefinite incarceration for journalists or academics, throwing rocks is another form of expression for a repressed population, articulation of self-representation, a distinct type of reclamation of social space and of power. "/>

7. Pathraao – Responding From A Rock Hard Place:

red cheeks,

blood shot eyes,

red is the color of chillies

drying in the golden sun

to grind,

red is on the mind.

rickety rocks,

red tick,

red tock,

red blood,

red shots,

one red head off,

one red head drops.

visible is the

red is on the roads,

blocked with red rocks.

Throwing rocks is a form of protest in public spaces for at-risk populations like Kashmiri youth to express dissatisfaction or dissent in a repressive war zone. Where the normalized patterns of everyday life include injured, disappeared, or missing kin and relations turning up murdered, dead, and buried, it’s an expression of anger, rage, and refusal to accept the status quo and systemic injustices by the youth. Rather than position these youth in their rightful context, these Kashmiris (primarily youth) doing ‘pathrao’ (throwing rocks) are presented as part of a colonial narrative of ‘those violent delinquent Kashmiris’ by the popular corporate media in India, and those seeking to repress public display of protests.

In a war zone where the military and police are found in every corner carrying a loaded gun, the use of which they are unlikely to be held accountable for by colonial state laws, the use of rocks by unarmed people to articulate a response is presented as abhorrent, and shocking ‘juvenile Kashmiri crime.’ In the past decade, a new set of laws/policies as well as programs have been instituted to criminalize Kashmiri youth who engage in doing pathrao, pathologizing their choice rather than critically situating them in their appropriate context of being at-risk youth in a war zone. These youth are incarcerated for short to long-term sentences. They are eventually offered (policed) reform programming, where they are required to demonstrate that they will abandon their ways characterized as ‘criminal’. A genocidal policy of the Indian regime: these Indigenous children are forcibly removed from their families.

Some still throw rocks, after returning. Those who are labelled second time offenders face harsher sentences, and sometimes face arbitrary, lawless, indefinite incarceration under the Public Safety Act.

There are dimensions to the pathrao beyond the binary of seeing pathrao as anti-colonial resistance: an articulation of dissent and refusal of injustice and indignities, or alternatively the colonial narrative that: these youth are engaging in criminal behaviour. Those who experience pathrao will tell you that the rocks don’t always just hurt who they’re intended to hurt, who they’re meant for. To me, these rocks articulate another form of self-determination: we throw rocks at your policy decisions of trying to erase us from our land. Where freedom of expression using words can result in indefinite incarceration for journalists or academics, throwing rocks is another form of expression for a repressed population, articulation of self-representation, a distinct type of reclamation of social space and of power.

If they spoke, what would the Kashmiri Mountain goats tell us about the silk routes in the Valley which is now a war zone? How are the routes of seasonal migration with the Gujjar families impacted by the war? Are the animals aware there is a war going on? Will the young ones ever know a time without war? Do they duck, and lay low at the sound of gun shots?

Animal herds of mountain goat, sheep, with ponies and dogs are not just ordinary migrating animals. In Kashmir, what we observe everywhere are beautifully mowed landscapes. The landscapes, where the vibrant green grass in the commons is trimmed in spring, summer, and fall, is not achieved by heavy-duty lawn mowing machines. Instead, it is achieved by the grazing of these migrating animals, whose petite feet and excrement pellets keep the soil fertilized. The animals on the move stay healthy as well.

The war has not been able to stop the seasonal migration, the grazing, or the bowel movements that lead to fertile health of the soil. However, the commons space is increasingly under attack by corporate interests inside and outside Kashmir, bought and sold, and hyper policed and regulated by the settler colonial Indian military state.

The intersection of communal and colonial violence in India affects the migrating Bakarwal families who are primarily Muslim, and targets of Hindu supremacists, especially in the Jammu region. For example, it was within this context that in January 2018, Asifa Bano, an 8-year old Muslim girl belonging to a Bakarwal family, was kidnapped and gang raped in a private Hindu Temple by Hindu nationalists in Rasana, near Kathua. The case led to significant upheaval in Kashmir, with many sectors of civil society protesting the gross injustices in how the case was handled.

While Bakarwals navigate risks to their survival in unique ways in the face of war, these remain the same old silk routes their ancestors travelled, and communicated knowledges about how to travel the pathways safely via the DNA of the migrating flocks intergenerationally. Kashmiris have had relations with the sacred mountain animals since time-immemorial. The animals Bakarwals shepherd have clothed and fed Kashmiri and non-Kashmiris since time immemorial. They represent self-determining continuity of tradition despite the odds against them, such as the increasingly colonial privatization of communal Kashmiri land. "/>

8. Mountain Goats - Mapping Kashmiri Land, Ancestral Memories, and Stories:

If they spoke, what would the Kashmiri Mountain goats tell us about the silk routes in the Valley which is now a war zone? How are the routes of seasonal migration with the Gujjar families impacted by the war? Are the animals aware there is a war going on? Will the young ones ever know a time without war? Do they duck, and lay low at the sound of gun shots?

Animal herds of mountain goat, sheep, with ponies and dogs are not just ordinary migrating animals. In Kashmir, what we observe everywhere are beautifully mowed landscapes. The landscapes, where the vibrant green grass in the commons is trimmed in spring, summer, and fall, is not achieved by heavy-duty lawn mowing machines. Instead, it is achieved by the grazing of these migrating animals, whose petite feet and excrement pellets keep the soil fertilized. The animals on the move stay healthy as well.

The war has not been able to stop the seasonal migration, the grazing, or the bowel movements that lead to fertile health of the soil. However, the commons space is increasingly under attack by corporate interests inside and outside Kashmir, bought and sold, and hyper policed and regulated by the settler colonial Indian military state.

The intersection of communal and colonial violence in India affects the migrating Bakarwal families who are primarily Muslim, and targets of Hindu supremacists, especially in the Jammu region. For example, it was within this context that in January 2018, Asifa Bano, an 8-year old Muslim girl belonging to a Bakarwal family, was kidnapped and gang raped in a private Hindu Temple by Hindu nationalists in Rasana, near Kathua. The case led to significant upheaval in Kashmir, with many sectors of civil society protesting the gross injustices in how the case was handled.

While Bakarwals navigate risks to their survival in unique ways in the face of war, these remain the same old silk routes their ancestors travelled, and communicated knowledges about how to travel the pathways safely via the DNA of the migrating flocks intergenerationally. Kashmiris have had relations with the sacred mountain animals since time-immemorial. The animals Bakarwals shepherd have clothed and fed Kashmiri and non-Kashmiris since time immemorial. They represent self-determining continuity of tradition despite the odds against them, such as the increasingly colonial privatization of communal Kashmiri land.

Experiencing Kashmir as a war zone at night is complex. What does the night permit and limit?

It sounds like echoes of hundreds of ping pong balls dropping. Are these machine guns going off again, people ask. Some lay in bed, half asleep, wondering, ‘are these trauma hallucinations’? They will know in the morning. Some go back to sleep, and others can’t fall asleep. With agitation, sleeplessness, some pick up the mobile phone to check if the mobile internet has snapped. If yes, they conclude that those must have been machine guns.

Next set of concerns, who was killed? How many? Why? Is there a curfew/hartaal/shut down tomorrow where I live, or where I am going? Does that mean all plans are cancelled? Will businesses remain open or will they be closed? Are schools open or closed? Will I make it alive if I go out?

In the villages of Kunan and Poshpora, the military ordered mass rapes of Muslim Kashmiri women during the night in 1991 (Mushtaq et al 2015). When you hear a woman’s loud cries at night in a Kashmiri neighbourhood, you wonder what violence has met her. Rejecting the narrative of being just the victimized, these women have been resisting and demanding justice for more than two decades, without success in the Indian legal system. The Indian soldiers who perpetrated this sexual violence to terrorize the locals as a weapon of war, they enjoy impunity from having committed war crimes.

What does the night permit, and limit?

Nights turn into days, days turn into nights, and war crimes are protected by legalized impunity. There is zero accountability. Despite this, radical Kashmiri anti-colonial resistance and self-determination looks like actively seeking, and demanding justice, dignity and accountability anyway. "/>

9. Noises that Keep You Awake - The War Doesn't Stop at Night:

Experiencing Kashmir as a war zone at night is complex. What does the night permit and limit?

It sounds like echoes of hundreds of ping pong balls dropping. Are these machine guns going off again, people ask. Some lay in bed, half asleep, wondering, ‘are these trauma hallucinations’? They will know in the morning. Some go back to sleep, and others can’t fall asleep. With agitation, sleeplessness, some pick up the mobile phone to check if the mobile internet has snapped. If yes, they conclude that those must have been machine guns.

Next set of concerns, who was killed? How many? Why? Is there a curfew/hartaal/shut down tomorrow where I live, or where I am going? Does that mean all plans are cancelled? Will businesses remain open or will they be closed? Are schools open or closed? Will I make it alive if I go out?

In the villages of Kunan and Poshpora, the military ordered mass rapes of Muslim Kashmiri women during the night in 1991 (Mushtaq et al 2015). When you hear a woman’s loud cries at night in a Kashmiri neighbourhood, you wonder what violence has met her. Rejecting the narrative of being just the victimized, these women have been resisting and demanding justice for more than two decades, without success in the Indian legal system. The Indian soldiers who perpetrated this sexual violence to terrorize the locals as a weapon of war, they enjoy impunity from having committed war crimes.

What does the night permit, and limit?

Nights turn into days, days turn into nights, and war crimes are protected by legalized impunity. There is zero accountability. Despite this, radical Kashmiri anti-colonial resistance and self-determination looks like actively seeking, and demanding justice, dignity and accountability anyway.

I witnessed Kashmiris rejecting the colonial state order on walls across Kashmir, with messages such as ‘Go India, Go Back.’ It was also reflected on the back of a car, and on the title of a burnt-down store. The back of the car read, “We Don’t Surrender / We Win Or Die,” and on the burnt store it read, “WAR TILL VICTORY.” I noticed that Kashmiris exercise the freedom to live and express themselves, before they experience an impending unjust murder by the Indian colonial occupier. Despite the expected violent backlash by the Indian military or police state, this visible political expressions of self-determination in Kashmir was still observable in September 2018. The frequency of witnessing these displays depends on the political climate and the neighbourhood of the Valley you are in.

Economically well-off neighbourhoods and communities enjoy greater human security in Kashmir; called ‘collaborators’ or ‘clients,’ their proximity to colonial power often entails greater intimacy and dependency on the colonial-masters.

I see self-determining Kashmiris humanize themselves by feeling the trauma wounds, fear, and moving past the fear by articulating their movements demands despite the colonial surveillance state repression and violences. "/>

10. Freedom of Expression:

I witnessed Kashmiris rejecting the colonial state order on walls across Kashmir, with messages such as ‘Go India, Go Back.’ It was also reflected on the back of a car, and on the title of a burnt-down store. The back of the car read, “We Don’t Surrender / We Win Or Die,” and on the burnt store it read, “WAR TILL VICTORY.” I noticed that Kashmiris exercise the freedom to live and express themselves, before they experience an impending unjust murder by the Indian colonial occupier. Despite the expected violent backlash by the Indian military or police state, this visible political expressions of self-determination in Kashmir was still observable in September 2018. The frequency of witnessing these displays depends on the political climate and the neighbourhood of the Valley you are in.

Economically well-off neighbourhoods and communities enjoy greater human security in Kashmir; called ‘collaborators’ or ‘clients,’ their proximity to colonial power often entails greater intimacy and dependency on the colonial-masters.

I see self-determining Kashmiris humanize themselves by feeling the trauma wounds, fear, and moving past the fear by articulating their movements demands despite the colonial surveillance state repression and violences.

This photograph illustrates a type of power exercised through social solidarity. In Kashmir, you witness it in the face of trying circumstances, despite the colonizer financing systemic infiltration efforts to divide Kashmiris. The popular phrase ‘adjust karsa’ (one translation of karsa is: make it happen) is often evoked as a trusted Kashmiri saying when trying to create space when there might not be any. I imagine here that these men might have said to each other, one by one, adjust karsa, on an evening commute to home when travelling by this bus.

As an exercise in hospitality, it is not limited to Kashmiris supporting each other, it is also extended to anyone – Kashmiris and non-Kashmiris alike - who are perceived to experience a relative under-privileged positionality in a social circumstance. Sometimes the adjustment is uncomfortable; people adjust even when they do not necessarily want to.

‘Adjust karsa’ is what the elder woman at the hospital who needed to sit down might have said to squeeze in to sit on the bench. It is what the bodies that piled up to protect each other from cold did during a mass funeral of a young man, when there was not enough room to get a clear view of the procession. It is what people huddled together in-community to take heat from a burning fire may have said, just to get a little closer to warmth.

Kashmiris have collectively adjusted to uncomfortable and trying social circumstances as a temporary coping mechanism, but ultimately, what they want is justice, dignity, and security. What does self-determined justice, dignity, and security look like from a Kashmiri standpoint? As the time-old Kashmiri protest chant demands: ‘hum kya chahte,’ what do we want, the response has always been: ‘Aazadi,’ liberation. "/>

11. Karsa Adjust:

This photograph illustrates a type of power exercised through social solidarity. In Kashmir, you witness it in the face of trying circumstances, despite the colonizer financing systemic infiltration efforts to divide Kashmiris. The popular phrase ‘adjust karsa’ (one translation of karsa is: make it happen) is often evoked as a trusted Kashmiri saying when trying to create space when there might not be any. I imagine here that these men might have said to each other, one by one, adjust karsa, on an evening commute to home when travelling by this bus.

As an exercise in hospitality, it is not limited to Kashmiris supporting each other, it is also extended to anyone – Kashmiris and non-Kashmiris alike - who are perceived to experience a relative under-privileged positionality in a social circumstance. Sometimes the adjustment is uncomfortable; people adjust even when they do not necessarily want to.

‘Adjust karsa’ is what the elder woman at the hospital who needed to sit down might have said to squeeze in to sit on the bench. It is what the bodies that piled up to protect each other from cold did during a mass funeral of a young man, when there was not enough room to get a clear view of the procession. It is what people huddled together in-community to take heat from a burning fire may have said, just to get a little closer to warmth.

Kashmiris have collectively adjusted to uncomfortable and trying social circumstances as a temporary coping mechanism, but ultimately, what they want is justice, dignity, and security. What does self-determined justice, dignity, and security look like from a Kashmiri standpoint? As the time-old Kashmiri protest chant demands: ‘hum kya chahte,’ what do we want, the response has always been: ‘Aazadi,’ liberation.

by Binish Ahmed

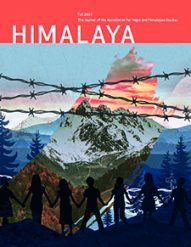

This photo essay consists of a sample of photographs I took, highlighting dimensions of life in Indian occupied Kashmir — a war zone where an anti-colonial resistance movement for self-determination by an Indigenous people (Ahmed 2016, Ahmed 2018a, Ahmed 2018b, Ahmed 2019b) is being violently repressed by an occupying, genocidal colonial Indian regime. Kashmiris are an Indigenous nation (Ahmed 2019) who have had much written about them from a deficit and ‘damage-centric’ (Tuck 2009) analytical lens, by insiders and outsiders. Rarely do we see the Kashmiri self-determination movement properly placed in its rightful place of an Indigenous anti-colonial resistance struggle, rooted in this native populations’ sovereign relation with their ancestral lands. Even though India is a signatory to the United Nations Declarations for the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), it does not internally recognize Kashmiris or others who the Indian state defines as ‘tribal’ and ‘backward’ in its legal framework as Indigenous peoples, who have sovereignty and inherent rights to their ancestral lands. While Indian legal definitions have yet to catch up, ratify, and comply with UNDRIP, in India Indigenous peoples are targets of state sanctioned violence intended to annihilate and forcibly remove them from their ancestral lands for capitalist, extractive, settler colonial ‘corporate economic development’ interests of dispossession and displacement (Ahmed 2016, Ahmed 2019b). Whereas the popular narratives and representations about Kashmiris is that they are powerless people, what I offer instead in this essay is a complex visual and analytical look at power and control in contemporary Kashmir. In this photo essay, I employ a qualitative Indigenous Anishnaabe symbol-based reflection method (Lavallée 2009), similar to a photo voice approach, where I display a series of frames of photographs I took in September 2018 in Kashmir to present critical knowledges about community issues that involve how public spaces, places, and gazes intersect to construct as well as produce distinct dimensions of genocidal colonial social order and control in a militarized Indigenous peoples homeland. What is implicit in this reflection essay is that the restrictions and permissions that produce the social order are a result of formal and informal policy regulations in place. When I employ the term ‘policy regulations’ that exercise power, I am referring to three types of social order policy practices: those policy practices that stem from the state’s administration and control of space as well as people; those policy practices that stem from self-determining community as subaltern practices, transcending the state, embodied in people as a collective; and last but not least, those practices which once again transcend the state, and are rooted in a type of individual power, located in human and non-human lives/bodies. What I offer in this essay are complex representations of power in Kashmir as a war zone, where an Indigenous nation asserts nuanced modalities of self-determination as anti-colonial resistance via public spaces, places, and gazes, in spite of the violent repression by the genocidal settler colonial Indian state. The captions of the photographs should be read as a critical, questioning/inquiring, analytical, ethnographic, poetic voice of a Kashmiri woman.

Binish Ahmed ([email protected]) is a Kashmiri educator, artist, researcher, writer, and a community connector. Her work looks at justice in governance, and social movements at the intersections of racialization, migration, labour, gender, Indigenous resurgence, and solidarity. She is currently completing a PhD (ABD) in Policy Studies at Ryerson University. She is the host of Azaadi Now, an independent Kashmiri broadcast (@AzaadiNow on Twitter). You can reach her by email, or on Twitter (@binishahmed), or Instagram (@subalternspeaking). This essay was submitted to HIMALAYA in May 2019.

References

Ahmed, Binish. Sept 30, 2019a. “Kashmir: If People You Know That Exist, Don’t Exist Anymore, Do They Still Exist.” Accessed on 22 October 2020. Amnesty International India. https://amnesty.org.in/kashmir-if-people-you-know-that-exist-dont-exist-anymore-do-they-still-exist/.

Ahmed, Binish. Aug. 8, 2019b. “Call the crime in Kashmir by its name: Ongoing Genocide.” The Conversation. Accessed on 22 October 2020. theconversation.com/call-the-crime-in-Kashmir-by-its-name-ongoing-genocide-120412.

Ahmed, Binish. 2018a. “Land and Bodily Sovereignty: Policy Problem Re-Framed via the Art of Refusing Empire and Embracing MADness”. Critical Insurrections: Decolonizing Difficulties, Activist Imaginaries, and Collective Possibilities. Peer reviewed conference at the University of British Columbia, Vancouver, June 23.

Ahmed, Binish. 2018b. “Asian and Indigenous: Re-Possession and Refusals of a Kashmir Womxn”. Critical Insurrections: Decolonizing Difficulties, Activist Imaginaries, and Collective Possibilities. Peer reviewed conference at the University of British Columbia, Vancouver, June 24th.

Ahmed, Binish. 2016. “Coming into an anti-colonial Solidarity Consciousness”. The Decolonization Conference, University of Toronto, Ontario, Nov 4.

Association of Parents of Disappeared Persons [APDP]. n.d. “About.” Association of Parents of Disappeared Persons (APDP). Accessed on 15 March 2019. http://apdpkashmir.com/about/”>http://apdpkashmir.com/about/.

Lavallée, Lynn. F. 2009. Practical application of an Indigenous framework and two qualitative Indigenous research methods: Sharing circles and Anishnaabe symbol-based reflection. International Journal of Qualitative Methods 8(1): 21-36.

Mushtaq, S., Batool, E., Rather, N., Butt, I., and M. Rashid. 2015. Do You Remember Kunan Poshpora?: The Story Of A Mass Rape. Zubaan Books.

Tuck, Eve. 2009. Suspending Damage: A Letter to Communities. Harvard Educational Review 79(9), Fall.

United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights [UNHCHR]. July 2019. “Update of the Situation of Human Rights in Indian-Administered Kashmir and Pakistan-Administered Kashmir from May 2018 to April 2019,” Office of the High Commissioner of Human Rights, United Nations. Accessed on 01 July 2019. https://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Countries/PK/KashmirUpdateReport_8July2019.pdf.

United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights [UNHCHR]. June 2018. “Report on the Situation of Human Rights in Kashmir: Developments in the Indian State of Jammu and Kashmir from June 2016 to April 2018, and General Human Rights Concerns in Azad Jammu and Kashmir and Gilgit-Baltistan,” Office of the High Commissioner of Human Rights, United Nations. Accessed on 10 August 2018. https://www.ohchr.org/EN/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=23198%20.

United Nations, Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples [UNDRIP]. 2008. Resolution adopted by the General Assembly, 107th plenary meeting, 13 September 2007. New York: United Nations. http://www.un.org/esa/socdev/unpfii/documents/DRIPS_en.pdf

Wani, Z. A., Hussain, A., Khan, A. W., Dar, M. M., Khan, A. Y., Rather, Y. H., and S. Shoib. 2011. Are Health Care Systems Insensitive to Needs of Suicidal Patients in Times of Conflict? The Kashmir Experience. Mental Illness Journal 3(1): e4.