Photo Essay

Inheriting Winemaking: Cizhong ‘Rose Honey’ Wine Production on the Upper Mekong River in Northwest Yunnan Province, China

A company hired Wu Gongdi’s family to make wine for its employees as an annual bonus gift. The mini-barrels the company used to hold the wine are labeled ‘Cizhong Chateau.’

In 2014, Wu Gongdi’s family also began experimenting with storing and fermenting wine in oak barrels for the first time, as part of an agreement with a corporation in the provincial capital that hired his family to make wine as gifts for their employees. The ratio of production of the wine is 1 kilo of raw grapes for every half liter of finished product.

Long awaited grape wine after a month of fermentation.

Third Step

The liquid becomes the final wine product after the endeavors above and is stored in clay jars for storage, sale, and display. Typically, it might be fermented enough and drunk and sold as early as 3-4 months after first being made.

Bamboo is wrapped around the end of the tubes as a filter while pumping fermented wine.

The filtration and sieving process is repeated several times until the wine becomes a pure liquid free of sediment.

Pumping the fermented wine from the barrel containing sediments of grape seeds and skin.

In order to filter the wine it is siphoned out into small basins or barrels from the larger buckets using a plastic tube. Any leftover grape skins and seeds sieved out are also saved and stored in a bucket for later grape liquor distillation. The filtered wine is then poured back into the buckets and sealed tightly with plastic film again to ferment.

Sieving the fermented wine.

Second Step

After being left to ferment for three to ten days, the length depending upon the maturity and sweetness of the grapes, the wine is filtered or sieved through bamboo baskets and cheesecloth.

Wu Gongdi’s daughter-in-law testing the degree of fermentation.

Additionally, most villagers including Wu Gongdi add sugar when they crush the grapes, indicating that this helps with fermentation and increases sweetness. Indeed ‘Rose Honey’ itself is a rather sweet varietal of grape and makes a better dessert wine over a dry wine in the views of the authors.

Sealing the crushed grape juice, seeds, and skin for fermentation.

After crushing the leftover stems are picked out of the basins, leaving the grape juice and sediments of grape skins and seeds, which are poured into large plastic buckets.

Wu Gongdi’s daughter-in-law crushing grapes, while he himself picks out the stems from the already crushed fruit.

Some seniors have recalled that locals previously chose to use a large wooden stick to crush grapes in wooden barrels before the 1950’s. The wooden basins have been abandoned for weight consideration and economics in contemporary times.

Wu Gongdi’s family crushing grapes.

After piling all of the grapes harvested from the vineyards in the household courtyard, the grapes are crushed by hand in large plastic or metal basins.

Grape harvesting: Process of Making Red Wine.

First Step

Winemaking begins by harvesting of the grapes, which are picked from the vines by the bundle, placed in bamboo or plastic baskets and then carried home with the basket on one’s back. All five members of Wu Gongdi’s family were actively involved in this stage of harvesting; even his granddaughter and grandson copied the others’ actions.

Picking the stems from the crushed grapes.

However, In Cizhong the situation is quite different than in other parts of Deqin. While some households do indeed grow some government introduced Cabernet cultivar with the use of chemicals, other choose to grow mostly ‘Rose Honey,’ which can be done entirely organically. Household agriculture in Cizhong also remains quite diverse, with large quantities of rice, wheat, barley, corn, and vegetables grown alongside vineyards, making food security a non-issue compared to other villages where grapes are monocroped. Additionally, while small quantities of Cabernet grapes grown in Cizhong are sold to the Shangri-La Wine Company, the majority of households use their grapes exclusively for winemaking, with the sale of wine making a great difference in annual household income. For Wu Gongdi’s family, wine, which is sold not only to tourists but also to restaurants and to large companies as annual employee gifts, is the largest source of annual income, with revenue from the sales going into his two granddaughters’ primary school education and living expenses in the local county town. In addition to regular grape wine, Wu Gongdi has also been testing production of ice wine, grape liquor distilled from the leftover skin and seeds, as well as ‘Rose Honey’ grape jam.

Wu Gongdi’s and his son Hongxing’s wine in a barrel and a Cizhong labeled bottle.

Most households in Cizhong produce relatively small amounts of wine compared to Wu Gongdi and only sell to visitors and also sell some grapes to the local Shangri-La Wine Company. The Shangri-La Wine Company is a recent development throughout the lowland river valleys of Deqin County where Cizhong is located. Developed in the early 2000’s by the local government as a poverty alleviation scheme, the company and the county government have promoted the conversion of traditional agricultural fields of barley and wheat throughout Deqin into monocroped vineyards. In most villages the grapes produced in these vineyards are sold directly to the company for winemaking rather than being used for household winemaking as they are in Cizhong. While the growing of grapes has overall led to higher annual incomes for households throughout the region, there have been drawbacks in terms of sustainability and food security. Having abandoned the production of grains for subsistence consumption, households are reliant on the sale of grapes to purchase food, and the Shangri-La Wine company does not have guaranteed contracts with villagers from one year to the next, often showing up late to purchase grapes after they have ripened and begun to dry out. In addition, the grapes introduced to Cizhong more recently and to other villages by the government and the company are of a different Cabernet variety, which requires heavy use of chemical pesticides and fertilizers. For more detailed information and these agricultural transformations in Deqin County associated with viticulture, see (Galipeau 2015).

Wu Gongdi’s wife vigorously crushing grapes.

With keen entrepreneurial talent and as an expert of grafter of fruit trees, Wu Gongdi, the director of the Cizhong Church Management Committee, started to learn to make wine from his aunt, who was a nun with the French and Swiss fathers in the upstream community of Yanjing in Tibet, prior to the 1950s. Wu Gongdi pioneered ‘Rose Honey’ grape cultivation with seedlings and cuttings taken from the original walled church vineyard in Cizhong’s church grounds in 1998. His family currently plants 8 mu (5333 square meters) of vineyards terraced along slopes below the forested mountains next to his house. From 1998 to the present, Wu Gongdi’s family has produced an average of 2000 kilos of wine per year, one of the largest annual household wine outputs in Cizhong. It is agreed among domestic and foreign visitors that the alcohol content is between 10-20%, one alcohol company specifically measured the alcohol content of Wu Gongdi’s wine as 18% in December 2014. The wine also fluctuates in taste and quality. Households all over Cizhong Village sell home-produced wine, and villagers are very proud of their ability to produce natural and organic products, contrary to other wine found in the region and discussed below.

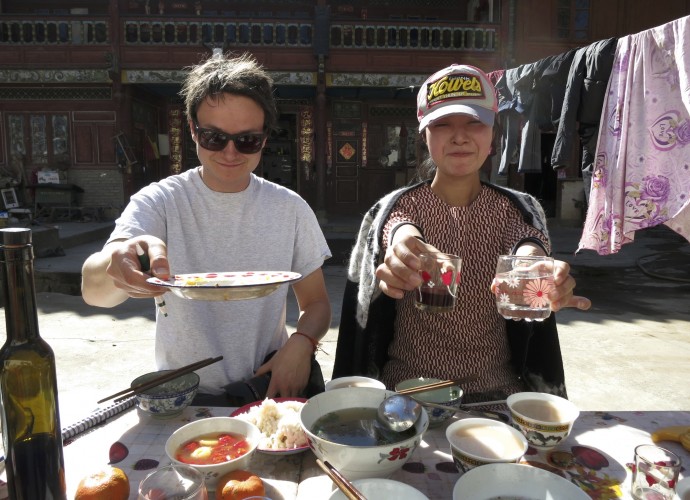

Wine in Cizhong turns into a must serve beverage during village weddings.

Today grape wine has also become an item in daily household consumption among some families, though particularly during festivals such as weddings where it is consumed in abundance. With the development of local tourism based around Cizhong’s unique history, the local wine has also become a souvenir for Han Chinese and international visitors. The rest of this photo essay describes the production of wine by Wu Gongdi’s family in Cizhong in September 2014. This family has been recognized as the first to procure ‘Rose Honey’ grapes from the remnant churchyard vineyards in 1998 to develop wine as a touristic product, a practice that is now almost ubiquitous among all of Cizhong’s households.

Bottling ‘Cizhong’ labeled grape wine.

Similarly, Wu Gongdi, whose household winemaking is discussed below and who is recognized as the first villager to renew a winemaking tradition in 1998, has also discussed wine, Catholicism, and local culture as being heavily linked together:I think Catholic culture is part of Tibetan culture, so wine is also part of Tibetan culture. But you also can’t talk about wine without talking about Catholic mass. The fathers who were here even learned to speak Tibetan and I think this also makes wine part of Tibetan identity here…We were the first family to regularly make wine, so for my family yes, it is very important to our identity.

An 86-year old devout catholic elder and local historian who used to assist the French and Swiss fathers before the 1950s.

Most households are engaged in the practice of winemaking, and keep vineyards and small cellar spaces in their homes. Cizhong wine is purely handmade using simple techniques. It is a rural household industry using some techniques whose earliest historical references can be traced back to the Catholic missionaries over a hundred years ago. The original use of wine in Cizhong was purely ritual-based; for mass in the village church. As one village elder who studied with the French and Swiss missionaries prior to the 1950’s and is now renowned as a local historian has stated:Wine is important to local culture because it is needed for Catholic mass, and this ritual can’t take place without wine. Wherever there is a church there is a vineyard; wine is not for play, it is for ritual. The French brought grapes overland from Vietnam, Nepal, and Tibet. These fathers traveled and brought grapes and wine to Sichuan and Tibet earlier before their arrival in Cizhong.

Collecting ‘Rose Honey’ grape cuttings from the walled church yard vineyard.

Winemaking is an important cultural activity in Cizhong. For over a decade, it has been used in daily household consumption and to serve guests who visit the village, which receives large numbers of tourists each year. Because of its association with village religious identity, wine is a very popular drink to serve to guests. Furthermore, Cizhong villagers are eager to share and discuss the history of wine and winemaking with visitors.

Cizhong Church built with Western and Chinese architectural styles.

The village of Cizhong is situated along the upper Mekong River in Diqing Tibetan Prefecture of Northwest Yunnan Province. A unique feature of Cizhong is that the community consists of many Tibetan Catholics, a religion that French and then Swiss missionaries introduced in the late 19th and early 20th centuries (Deshayes 2008; Lim 2009). This is highly unusual in and of itself since Tibetans are known worldwide as devout Buddhists. Additionally, the Catholic missionaries introduced grape cultivation and winemaking to this village; both practices that have been revived and carried on by villagers today in response to increasing tourism interest in Cizhong and its Catholic history.

Cizhong Church built in 1909.

Wine in Cizhong village is made of grapes, primarily from a variety known as ‘Rose Honey’ that was introduced to the Tibetan areas of Yunnan Province by French and Swiss Catholic missionaries over a century ago. This Vitis cultivar is thought to contain at least some DNA from the species vinifera hybridized with other unconfirmed species, though its definitive origin is still unknown. Assumed to be of missionary introduction and previously grown in Europe, it was wiped out by a blight and earlier thought to be extinct (Dangl 2011). By a twist of fate it still exists, but only in Yunnan Province (Galipeau 2015).by Fei Sun and Brendan A. Galipeau, this photo essay describes the history and process of grape wine production in Tibetan Cizhong Village of Northwest Yunnan Province, China. It follows and documents the annual winemaking tradition in one village household, and also provides photos showing the blending of wine into everyday village life, such as for wedding festivals and tourism promotion.

Keywords: China, Tibetan people, wine, agriculture, religion

All photos taken by the authors from August through December 2014.

Fei Sun

[email protected]

Brendan A. Galipeau (please direct all correspondence to this author)

[email protected]

Department of Anthropology, University of Hawaiʻi at Manoa

2424 Maile Way, Saunders Hall 346, Honolulu, HI 96822

Fei Sun (MPhil, Anthropology, Yunnan University, 2010) is a freelance anthropologist who has lived and worked in Yunnan Province on projects involving ethnicity, ecology, and environmental conservation for over ten years. He has consulted with and led expeditions and research trips for a variety of organizations including National Geographic Magazine, The Nature Conservancy, and the Joseph F. Rock Herbarium of the University of Hawaiʻi at Manoa.

Brendan A. Galipeau (MA, Applied Anthropology, Oregon State University, 2012) is currently a doctoral candidate in the Department of Anthropology at the University of Hawaiʻi at Manoa. His research interests and publications focus on environmental and economic anthropology of hydropower development, agricultural practices, and non-timber forest products in Southwest China. His current dissertation research explores economic and ecological commodification as modes of indigeneity and identity formation as they relate to agricultural change of red wine and grape production among Tibetans in Southwest China.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Hongxing, the trekking guide, for his hospitality while visiting his home during the winemaking season, and for his insightful contributions to the information in this photo essay. Appreciation also to Wu Gongdi for patiently explaining the processes of wine making. Inspiration was also drawn from a previous article by (Delang 2008) on rice whiskey production in Northern Laos as cited in the list of references below. Helpful comments were also provided by three reviewers from the journal Ethnobotany Research & Applications.

Endnote

We use Wu Gongdi’s and his son Hongxing’s real names by their own request, as cultural informants. Wu Gongdi is a public figure in Cizhong as the director of the church management association and has also been the main protagonist in two documentaries produced about Cizhong and Catholicism in Tibet by the Catholic Diocese of Hong Kong and the Yunnan Academy of Social Sciences (Liu 2002; The Way to Tibet 2004). Wu Gongdi and Hongxing are especially proud of their family’s wine and have asked us to use their real names when writing about them because they do indeed want people to know about their wine and their family’s story.

References

Dangl, Gerald. 2011. Tales from the FPS Plant Identification Lab. University of California Davis FPS (Foundation Plant Services) Grape Program Newsletter, October.

Delang, Claudio O. 2008. Keeping the Spirit Alive: Rice Whiskey Production in Northern Lao P.D.R. Ethnobotany Research and Applications 6: 459–70.

Deshayes, Laurent. 2008. Tibet (1846-1952); Les Missionnaires de l’impossible. Paris: Les Indes Savantes.

Galipeau, Brendan A. 2015. Balancing Income, Food Security, and Sustainability in Shangri-La: The Dilemma of Monocropping Wine Grapes in Rural China. Culture, Agriculture, Food and Environment 37 (2): 74–83.

Lim, Francis Khek Gee. 2009. Negotiating ‘Foreignness,’ Localizing Faith: Tibetan Catholicism in the Tibet-Yunnan Borderlands. In Christianity and the State in Asia: Complicity and Conflict, edited by Julius Bautista and Francis Khek Gee Lim, 79–96. London: Routledge.

Liu, Wenzeng. 2002. Christmas Eve in Cizhong, Cizhong Red Wine (Cizhong Shengdan Jie, Cizhong Hongjiu, 茨中圣诞夜, 茨中红酒). Baima Mountain Culture Research Institute.

The Way to Tibet. 2004. Audio Visual Center of the Catholic Diocese of Hong Kong.